Disordered Eating in General Practice

Approaching disordered eating in general practice

Disordered eating is common in UK general practice, but it rarely presents clearly or follows a linear path. It often sits behind other problems — menstrual disturbance, fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, diabetes control, parental concern — and unfolds over time rather than declaring itself in a single consultation.

The challenge for GPs is not diagnostic labelling, but recognising patterns, interpreting risk, managing uncertainty, and making proportionate decisions when patients or families are ambivalent, minimising, or resistant to change. Safeguarding considerations, follow-up planning, and clear explanation of clinical thinking are often more important than naming a specific eating disorder.

This resource is designed to support a practical, GP-focused approach to disordered eating as it is encountered in everyday practice. It emphasises recognition, longitudinal risk, consultation skills, safeguarding, and realistic management planning — with SCA-style cases included to reflect how these consultations are assessed in GP training.

It is aligned with the RCGP curriculum, NICE guidance, and UK safeguarding principles, and is relevant for ST1–ST3 and for GPs who want greater confidence in consultations that feel difficult to move forward, rather than unfamiliar.

How to use this resource

This pack is structured through seven learning resources

They are designed to work together, but you do not need to complete them in order.

If you already know where your gaps are, you can go straight to the section you need.

You can:

work through everything sequentially,

dip into a single resource for targeted learning.

Disordered Eating

Introduction & scope

What this resource covers (and doesn’t), definitions, framing disordered eating in GP practiceSafeguarding and disordered eating

Adults (vulnerability, capacity, self-neglect)

Children and young people (duties, Gillick competence, proportional action)Recognising disordered eating in general practice

Presentations, patterns, OSFED / atypical presentations

Medical risk recognition, gynae/fertility/amenorrhoeaFollow-up, uncertainty and escalation

Managing clinical uncertainty

Unsafe delay vs active monitoring

Escalation and reviewing with purposeConsultation skills in disordered eating

Sharing clinical thinking

Language and framing

IMP tensions and realistic management plansDisordered eating in the AKT

What is actually tested

Common pitfalls

Exam framing and sample questionsSCA role-play cases

For use in peer to peer practice with debrief notes

Disordered Eating - Introduction & Scope

Start here.

This short PDF sets the scene for the rest of the disordered eating resource. It explains an approach to the disordered eating that we’ll take. It will also set out the scope of this learning.

Reading this will give/refresh previous learning on disordered eating (also known as eating disorders) and is recommended as starting place.

Disordered Eating - Safeguarding & Disordered Eating

Safeguarding considerations are central to the assessment and management of disordered eating in general practice, but they are often poorly understood or avoided because they feel complex or high-stakes.

In reality, safeguarding in this context is usually about recognising vulnerability, preventing harm, and ensuring appropriate review and follow-up — not about blame, punitive action, or automatic referral to social services. This applies across the lifespan, with specific duties in children and young people, and different but equally important considerations for vulnerable adults.

This section outlines how safeguarding principles apply to disordered eating in everyday GP practice. It clarifies when and why safeguarding duties are triggered, how to act proportionately, and how to hold safeguarding alongside confidentiality, capacity, and patient autonomy. The aim is to support confident, defensible decision-making — particularly in consultations that feel uncertain or slow to move forward.

Click here to download this guide to Safeguarding & Disordered Eating

Medical emergencies in eating disorders (MEED)

GP escalation and safety reference

Eating disorders can deteriorate rapidly and unpredictably. This one-page wall chart translates the MEED (Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders) guidance into a GP-focused escalation aid, covering both adults and children and young people.

It is designed for use in clinical settings to support rapid decision-making when assessing medical risk, recognising when escalation is required, and avoiding false reassurances from normal weight, blood results, or apparent stability.

Use this resource to:

recognise features that require same-day hospital assessment

identify when urgent specialist input is needed

understand why follow-up is a safety intervention

support proportionate escalation in line with MEED principles

Download: MEED GP Wall Chart (PDF) Designed for printing and display in clinical areas.

Disordered Eating - Recognising it

Disordered eating rarely presents as an explicit concern in general practice. It is more often identified through patterns over time — menstrual disturbance, fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, diabetes control, parental concern, or repeated reassurance from normal results.

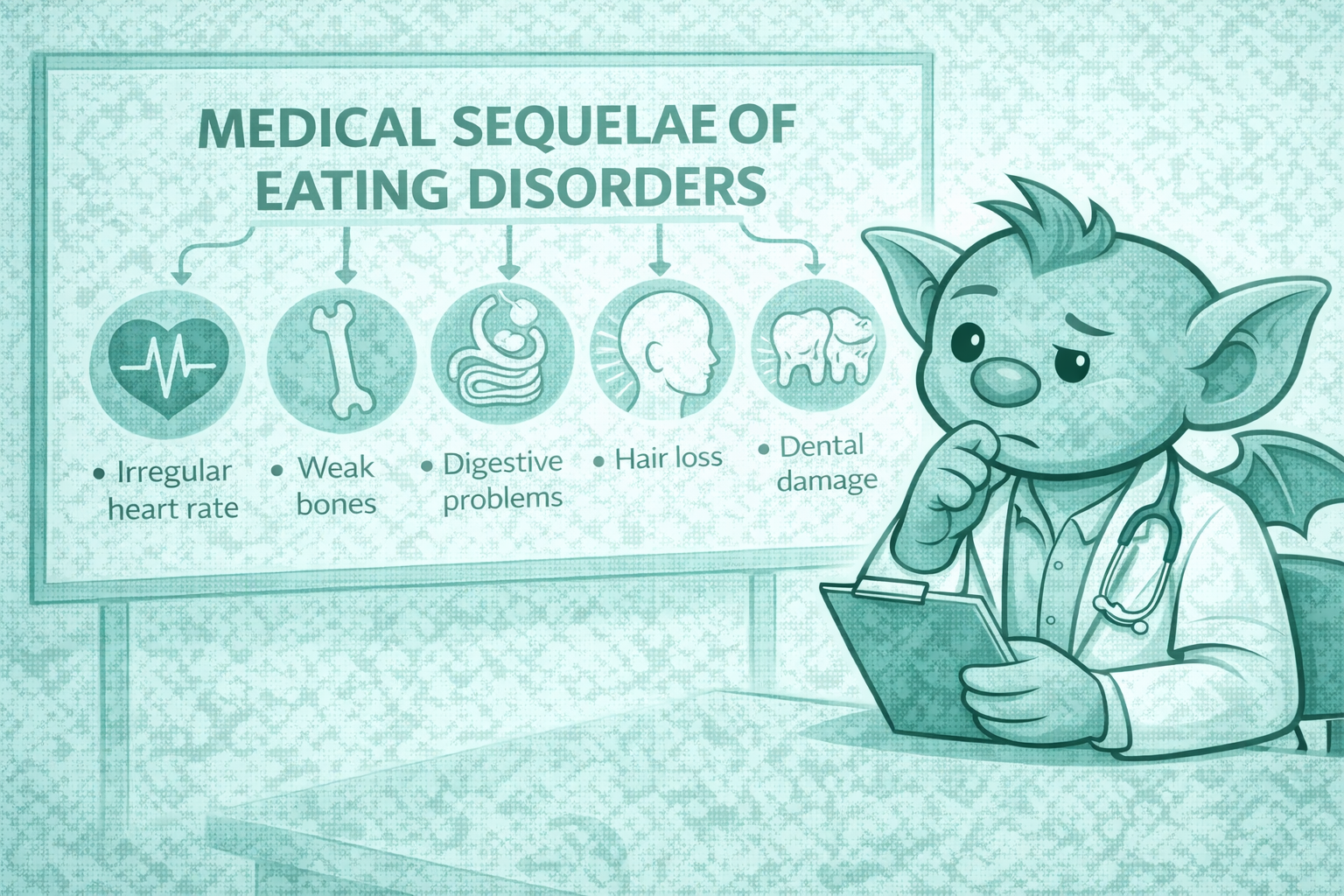

This presentation focuses on how disordered eating commonly appears in GP consultations, including atypical and OSFED presentations, early medical consequences, and risk indicators that matter more than weight or diagnostic labels. The emphasis is on recognising concern, interpreting risk, and understanding when a pattern should prompt further assessment or follow-up.

It is designed to support day-to-day clinical judgement and complements later sections on safeguarding, follow-up, and consultation skills.

-

Disordered eating often evolves over time, and risk may increase even when presentations appear stable.

In general practice, disordered eating is rarely resolved in a single consultation. Patients may present early, share some information but not all, or move between engagement and minimisation. Medical risk and safeguarding concerns often emerge over time, rather than being obvious from the first appointment

Follow-up matters because:

risk can accumulate quietly, even when symptoms appear unchanged

patterns only become visible with multiple consultations, not from a single snapshot

apparent stability can mask ongoing restriction, compensatory behaviours or deterioration

early reassurance may delay necessary escalation

In contrast to acute care, general practice is uniquely placed to notice:

repeated low-grade attendance

gradual shifts in behaviour, weight, function or physical symptoms

increasing clinician concern despite “similar” presentations

Follow-up is therefore not a passive process. It is an active clinical intervention, allowing the clinician to:

reassess risk as behaviours evolve

notice when engagement is not translating into change

recognise when concern is increasing, even if objective markers lag behind

A key challenge in disordered eating is that lack of deterioration is often mistaken for safety. In reality, unchanged symptoms may reflect:

entrenched behaviours

ongoing physiological stress

delayed consequences

Planned, purposeful follow-up allows clinicians to move beyond single-consultation decision-making and respond to the trajectory, not just the moment.

-

This section explores how to work safely when concern is present but there is no immediate crisis.

A common challenge in disordered eating is managing situations where risk is real, but urgency is unclear. The patient may not be acutely unwell, investigations may be reassuring, and there may be no single trigger for emergency admission — yet something does not feel right.

This uncertainty is a normal part of general practice. It often arises when:

behaviours are concerning but not extreme

symptoms fluctuate rather than progress clearly

the patient is engaging but not changing

risk feels cumulative rather than acute

The danger in these situations is drifting into passive waiting, where uncertainty leads to repeated reassurance without a clear plan. Over time, this can allow risk to increase unnoticed.

Managing uncertainty safely involves:

acknowledging that not being an emergency does not mean low risk

being explicit (to yourself and the patient) about what you are monitoring

setting a clear timeframe for review, rather than open-ended follow-up

noticing whether your level of concern is increasing, even if the presentation looks similar

It can be helpful to name uncertainty internally:

“I don’t think this needs emergency admission today, but I’m not comfortable leaving this without close follow-up.”

This framing supports proportionate action without overreacting.

Uncertainty should prompt structured monitoring, not inaction. Over time, patterns usually declare themselves — either through improvement, ongoing stagnation, or escalation of risk.

The key skill here is tolerating uncertainty without normalising risk. This allows clinicians to respond early when the situation changes, rather than waiting for a crisis to force action.

-

This section distinguishes active monitoring from delay that becomes unsafe over time.

In disordered eating, follow-up can look deceptively similar whether it is being used well or poorly. Both may involve review appointments, repeat conversations and ongoing reassurance. The difference lies in intent, structure and pace.

Planned follow-up is an active process. It involves:

a clear reason for reviewing again

an agreed timeframe, based on clinical concern rather than convenience

an understanding of what would prompt a change in plan

explicit attention to risk, not just symptoms

In contrast, unsafe delay often develops gradually. It may be characterised by:

repeated reviews with the same conversation, the same plan and the same outcome.

reassurance being repeated despite no or little improvement

concern being acknowledged but not acted on

a growing sense of “let’s see how things go”

Unsafe delay is rarely deliberate. It often reflects:

discomfort with escalation

hope that engagement alone will lead to change

uncertainty about thresholds

pressure to avoid over-medicalising

an unconscious drift towards maintaining rapport at the expense of changing the plan

A useful question to ask yourself is:

“Have I actively chosen this plan — or has it simply continued?”

Planned follow-up should feel purposeful. Even when change is slow, there should be clarity about:

what you are monitoring

why this pace currently feels safe

what would prompt you to reassess urgency

If follow-up no longer feels like it is moving the situation forward — or if your concern is increasing despite repeated reviews — this is a signal to change pace, not extend the same plan.

The status quo should not be reassuring. If things are not improving or progressing, a change in approach or escalation is required.

-

In disordered eating, lack of change does not mean lack of risk.

Risk in disordered eating is dynamic and cumulative. A presentation that looks unchanged from one review to the next may still represent a worsening clinical situation, even if behaviours appear stable and there has been no obvious deterioration.

This is because the risks associated with disordered eating accumulate over time. Ongoing restriction, purging or compensatory behaviours continue to place physiological and psychological strain on the body, even when the level of behaviour does not escalate.

In this context, lack of improvement is itself clinically significant.

At follow-up, it is important to look beyond whether symptoms are “the same” and consider:

whether behaviours are continuing without improvement

whether rigidity, control or preoccupation is persisting

whether physical symptoms are subtle but ongoing

whether function is being maintained at increasing personal cost

Risk may therefore increase despite:

stable weight or blood results

repeated attendance and engagement

the absence of new symptoms

A helpful way to think about this is to focus on trajectory rather than snapshot. Ask yourself:

Is this improving, or simply persisting?

Is the cumulative risk increasing because this is ongoing?

Re-assessing risk also includes noticing your own response as a clinician. If the plan has remained unchanged despite no improvement, or if reassurance is being repeated in the face of persistence, this is a prompt to pause and reconsider the approach.

In disordered eating, ongoing exposure to risk matters. When there is no meaningful improvement over time, a change in approach or escalation should be considered — even if the presentation has not become an emergency.

-

Partial engagement is common in disordered eating and does not reliably indicate safety.

Many patients with disordered eating engage with care in part. They may attend appointments, agree to monitoring, or acknowledge some concern, while still struggling to change behaviours. This pattern is expected and should not be interpreted as resistance or failure.

Ambivalence often shows up as:

agreeing with concerns but not acting on them

small, short-lived changes that are hard to sustain

selective disclosure of behaviours

reassurance-seeking alongside ongoing risk

It is important to recognise that engagement does not equal improvement, and that maintaining contact alone does not reduce risk.

A common challenge for clinicians is balancing:

the wish to preserve rapport and trust

the need to respond to ongoing or cumulative risk

When engagement is partial, there can be a subtle pull to slow the pace, soften concern, or continue the same plan in the hope that motivation will increase. Over time, this can unintentionally allow risk to persist without change.

Helpful questions to ask yourself include:

Is engagement translating into meaningful change?

Am I prioritising keeping the relationship comfortable over addressing risk?

Has my plan changed in response to ongoing behaviour, or just continued?

Managing ambivalence safely involves:

acknowledging the difficulty of change without minimising risk

being clear that concern remains even when engagement is good

revisiting goals and expectations explicitly

adjusting pace when partial engagement becomes prolonged

It can be helpful to name this dynamic calmly and transparently:

“I can see you’re trying to engage, and I’m still concerned about the impact this is having on your health.”

This keeps the focus on safety rather than motivation.

Partial engagement is a starting point, not an endpoint. When it persists without improvement, it should prompt a review of the plan and consideration of whether a different approach — or escalation — is needed.

-

Escalation is part of good care when risk increases or fails to reduce over time.

In disordered eating, escalation is often delayed not because risk is absent, but because the situation feels familiar, contained, or relationally complex. Changing gear can feel uncomfortable, particularly when a patient is engaging or the relationship feels fragile.

Escalation should be considered when:

medical risk is increasing or no longer feels manageable in primary care

behaviours are persisting without improvement despite follow-up

cumulative risk is rising over time

safeguarding concerns are emerging or intensifying

capacity to make or act on safe decisions is in doubt

Escalation is not a sign that earlier care has failed. It reflects a change in clinical need, not a breakdown in rapport.

A helpful reframing is:

“This has reached a point where it needs a different level of support.”

When escalation is needed, clarity helps:

be explicit with yourself about why the plan needs to change

explain the rationale to the patient in terms of safety

acknowledge the impact on the therapeutic relationship

document concerns and decision-making clearly

It is common for patients to feel disappointed, anxious, or resistant when escalation is discussed. These reactions do not invalidate the decision. Maintaining transparency and calm reassurance helps preserve trust even when agreement is limited.

Changing gear is often most effective when it is:

timely rather than reactive

proportionate rather than abrupt

framed as support, not punishment

Escalation is a clinical decision made in response to risk. Acting earlier can prevent crises and supports safer care for both patients and clinicians.

-

Clear documentation and safety-netting support safe care over time, particularly when risk is evolving.

In disordered eating, care is often shared across time, clinicians and settings. Good documentation and safety-netting are therefore essential to maintain continuity and reduce the risk of drift, repetition or missed escalation.

Documentation should make clear:

the concerns you have identified

the patterns you are noticing over time

your assessment of risk and uncertainty

the rationale for the current plan

what would prompt a change in approach

This helps ensure that concern is carried forward, rather than reset at each consultation.

Safety-netting should be explicit and proportionate. This includes:

clear advice about when to seek urgent review

planned review dates rather than open-ended follow-up

clarity about who the patient should contact if things worsen

shared understanding of what “getting worse” might look like

Continuity matters, but it cannot always be guaranteed. Helpful practices include:

documenting concerns clearly enough that another clinician can pick up the thread

avoiding reliance on unspoken assumptions or familiarity

recognising when repeated reassurance across clinicians may unintentionally dilute concern

It is also important to document changes in clinician concern, even when the presentation appears similar. An increasing sense of unease, frustration, or uncertainty is clinically relevant and should prompt reflection on whether the plan remains appropriate.

Good documentation and safety-netting do not replace clinical judgement — they support it. Together, they help ensure that evolving risk is recognised and acted on, even when care is shared or stretched over time.

-

This section offers prompts to help clinicians step back and reassess when care feels static or uncertain.

In ongoing care for disordered eating, it is easy to become focused on individual consultations rather than the wider picture. This final section is designed to support periodic re-evaluation, particularly when progress is slow or concern is persistent.

Helpful prompts include:

Is this genuinely improving, or simply continuing?

Has the level of risk changed because this has been ongoing?

Have I adjusted my plan in response to what I’m seeing?

Would I be comfortable if this approach continued for another few months?

It can also be useful to reflect on your own responses:

Do I feel increasingly uneasy, frustrated, or stuck?

Am I repeating reassurance because the situation feels familiar?

Am I holding risk because escalation feels difficult?

These reflections are not a sign of poor care. They are often an early signal that the current approach needs to be reviewed.

Re-evaluation does not always mean escalation. It may involve:

tightening follow-up

being more explicit about concern

revisiting expectations and goals

seeking senior or colleague input

What matters is avoiding default continuation of the same plan when it no longer feels right.

Regularly pausing to re-evaluate helps ensure that care remains responsive to cumulative risk, rather than anchored to the appearance of stability.

Escalation based on concern and trajectory , even without diagnostic certainty, is appropriate and expected in both independent practice and the SCA.

Disordered Eating: Follow up, Uncertainty & Escalation

Many consultations involving disordered eating sit in a grey area — not an emergency, but not straightforwardly reassuring either. Risk often emerges over time, through lack of improvement, repeated reviews with the same outcome, or increasing restriction that does not trigger immediate red flags.

This section focuses on how to manage uncertainty safely in general practice. It explores follow-up as an active clinical intervention, how to distinguish monitoring from unsafe delay, when to change approach, and how to escalate proportionately when progress stalls. The emphasis is on judgement, continuity, and decision-making over time, rather than single-visit thresholds.

It is particularly relevant for consultations that feel difficult to move forward, where doing nothing can quietly become a decision in itself.

Click the + icon to expand each section and explore practical guidance on follow-up, uncertainty and escalation in disordered eating.

Disordered Eating - Consultation Skills in Disordered Eating

Consultations involving disordered eating are often challenging — not because the clinical issues are unfamiliar, but because patient priorities may directly conflict with medical risk, and agreement is not always possible.

This section focuses on the consultation skills that are particularly important in this context: sharing clinical concern without diagnostic labelling, explaining risk clearly and proportionately, exploring impact and meaning, and developing realistic management plans that prioritise safety and follow-up. It emphasises that effective consultations may increase clarity rather than agreement.

The guidance is relevant to everyday GP practice and reflects how these skills are assessed in the SCA, where safe judgement, clear explanation, and proportionate planning matter more than resolution within a single consultation.

Disordered Eating in the AKT

In the AKT, disordered eating is rarely tested through detailed diagnostic criteria or specialist management. Instead, questions tend to assess whether candidates can recognise concerning patterns, interpret risk, and avoid false reassurance based on weight, blood results, or isolated symptoms.

This section highlights how disordered eating is examined in the AKT, the common traps candidates fall into, and how to frame questions to identify what is actually being tested. The focus is on applying general principles — recognition, interpretation, and safe decision-making — rather than memorising specific eating disorder diagnoses.

It is designed to complement the clinical and consultation-based sections of this resource and support confident, exam-ready reasoning.

SCA role-play cases (peer-to-peer practice)

These SCA-style cases are designed for peer-to-peer practice, without the need for a trainer or facilitator. Each case includes the information available to the doctor, a detailed patient (or parent) script, and a structured assessor brief with an SCA-aligned marking framework.

To use the cases effectively, work in threes. One trainee takes the role of the doctor, one plays the patient or parent using the script provided and the other one actively observe. After the consultation, the observer uses their own observations, the assessor brief and debrief prompts to reflect on clinical judgement, communication, and management decisions. The focus should be on safe reasoning and proportionate action, rather than reaching a diagnosis or resolving the problem within the consultation.

These cases reflect the level and style of the SCA, but are also intended to support real-world GP practice. Discomfort, uncertainty, and lack of agreement are built in deliberately — learning comes from how these are handled, not from “getting it right” quickly.

Disordered eating and diabetes

A GP approach to medical complexity

Disordered eating in people with diabetes represents a high-risk area of medical complexity in general practice. It often presents indirectly, through patterns of deteriorating control, inconsistent engagement, or distress around food, weight, and insulin — rather than as an explicit eating disorder concern.

This resource focuses primarily on Type 1 diabetes, where disordered eating can lead to acute metabolic risk and serious complications, including ketonaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis. It supports GPs in recognising concerning patterns, explaining risk clearly and non-judgementally, and knowing when follow-up or escalation is required. A short appendix addresses how the same principles apply in Type 2 diabetes, where the risk profile and thresholds differ.Use this resource to:recognise patterns that should prompt concern in diabetes reviewsunderstand why disordered eating in Type 1 diabetes requires a different risk lensdevelop consultation language that reduces shame and increases safetymanage uncertainty, follow-up, and escalation confidently in practice and exams

Download: Disordered Eating and Diabetes in General Practice (PDF)